Ricky Richard Anywar | Friends of Orphans (FRO)

Anywar 'Ricky' Richard

The Stolen Children

No matter how many times Ricky tells his story, it never loses its power. Imagine living a peaceful rural life, content and secure in the company of family and friends, unaware that evil would one day reach your doorstep.

“We heard there was a war in Uganda,” recalls Ricky, “but we couldn’t understand it. It was too far away.”

In his Northern Ugandan community, Ricky’s family enjoyed special status because his father’s work as a teacher and his mother’s as a farmer allowed them to own rare luxuries: a bicycle, and a radio that often drew neighbors to their house to gather around and listen to the news.

There were reports of fighting between government troops and rebels, of brutality and genocide, and of children as young as 8 being dragged from their homes and forced to become soldiers. In 1988, when Ricky was 14, that evil finally hit home.

“We heard the gun shots. I got scared. I knew that today we were going to be abducted,” remembers Ricky.

Instead of running, his parents defiantly stood their ground while rebels grabbed Ricky and his 16-year-old brother. The two boys were tied up while the rebels rounded up their parents and their three younger siblings, locking them into a grass-thatched hut and setting it ablaze. As Ricky and his brother watched, the Anywar family was burned alive.

“They were crying for help. It was the toughest moment I’ve seen in my life,” Ricky recalls.

For the next two and a half years, he and his brother endured relentless brutality and intimidation that would transform them into battle-hardened warriors in the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). Led by Joseph Kony, a self-proclaimed spokesperson for God, the LRA was fighting to overthrow Uganda’s secular government with an army of stolen children.

“I fought many wars; I passed through sprayed bullets and bombs from helicopter gunships. It was not an easy thing. I saw brutality beyond description. I saw tortures, rapes, killings and abductions. I was so scared, terrified and trembling. My brother and I had to keep reminding ourselves that if we get space, we should escape.”

Ultimately, they did—but there was a high price to pay for their freedom.

Friends of Orphans provides school supplies and scholastic materials to war affected children in Northern Uganda

The civil war in northern Uganda raged on for more than 20 years. 100,000 people died; more than 60-thousand boys and girls were dragged from their homes, schools and villages and marched to rebel hideouts deep in the bush. The boys were made to kill or be killed and the girls were used as sex slaves.

In 1991, Ricky’s brother made a daring escape. Three months later, Ricky also risked death and fled, making his way back to his home village. But instead of feeling jubilation, there was more traumatic news.

“I looked for my brother everywhere. A neighbor said he had fallen sick and was in the hospital. But one elder told me that Patrick had come home and committed suicide. They took me to his grave and I got totally broken down again. Coupled with what I saw in the bush, how my parents had been killed, now the death of my brother, I felt broken down. I felt that was the end of my life.”

In short order, Ricky was tracked down and recaptured by the LRA before he made his risky final escape. This time, the elders in his village gave him money and told him to go far away before the soldiers returned because they knew Ricky would be killed.

Ricky walked 18 miles before hitching rides in cars and buses to the city of Jinja, nearly 300 miles from his village. For a child of the bush, it was an overwhelming place where there was noise and traffic and people talking a language he didn’t understand. Ricky moved around the outskirts of the town, until ending up at a bus stop that turned out to be his first bit of good luck.

“At the bus stop, I heard people talking my language. I told them my story and that I wanted a job. One lady asked me if I wanted to work in a small gin factory. So I started working. I worked so hard for her. During the night I could work as a security guard and during the day I started learning how to brew gin. I never told anyone what happened to me. I was so ashamed that when I would think about it tears would begin rolling down my cheeks.”

Eventually, the woman asked Ricky what he wanted to do with his life. Ricky knew his parents always wanted him to be educated. So the woman agreed to sponsor him so he could go to school. In the years that followed, Ricky worked hard at school, earning a college degree and landing a good job in Uganda’s capital, Kampala, but home was never far from his thoughts. He felt compelled to return to the place where his happiest memories and his worst nightmares had happened, and where war was still devastating the lives of village children.

“When I told people in Kampala I was going back, they asked, why can’t you be here where it’s safe. But my heart was telling me I need to go back and help these children.”

In 1999, Ricky founded Friends of Orphans (FRO) with a mission to contribute to the empowerment, rehabilitation and reintegration of former child soldiers, abductees, child mothers, and orphans and to combat the spread of HIV/AIDS.

Friends of Orphans band marching at graduation

“As a former child solider, I fully understand the difficulties and suffering of children fighting alongside the Lord’s Resistance Army. It’s very difficult for someone to say, yes, I killed 100 people; it’s shameful. A girl cannot explain how they used her as a sex slave. They always fear to tell strangers what happened to them because they fear they are going to be prosecuted.

We gauge the level of trauma these people are holding. We give them opportunities to open up to us. And, in the process of rehabilitating them, we do psychological group and individual counseling, depending on each story.”

“The day I was abducted as child soldier I felt like a tree split from top to bottom by lightening,” says Ricky. But I was rescued and got the opportunity to go back to school, going all the way to university. The best thing is to give that empowerment to the children; to restore respect and dignity to them so they can live a life without exploitation, without discrimination, without abuse; to achieve their full potential and contribute to the development of their community.”

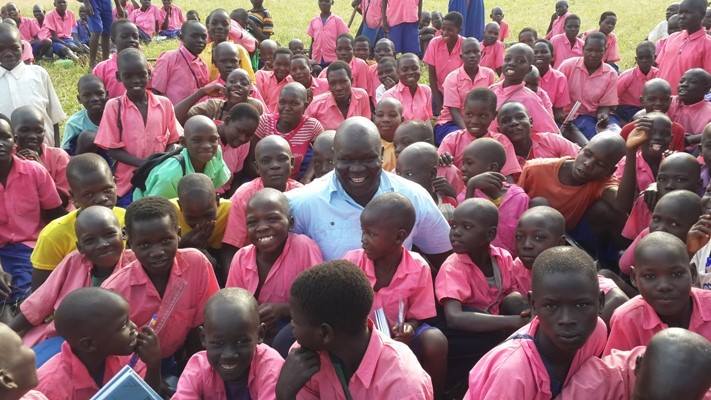

Ricky working with Friends of Orphan youth in northern Uganda

Friends of Orphans admits 400 young people every year with the hope of growing into an international organization to serve former child soldiers and child mothers all over the world. In addition to psychological support, over a 12-month period, the students are given vocational skills, life skills, basic reading and math instruction, as well as business management training.

“I saw from my own experience that if former child soldiers could be supported, they are still useful human beings and good citizens. I would like to give an opportunity for each of them so they can also still succeed in life.”

Ricky says changing from a lost “child soldier” to working to help people come out of their difficult situations has helped him cope with his own past trauma.

“When I look back at my past life and who I am now with a changed heart, l always feel joy. I know there are human beings who brutalized me, killed my people, made my childhood to be bad but there are human beings who helped me. A woman in America said she wanted to adopt me. So you see the beauty of human beings as well.”

Former child soldiers dancing during peace building program

Watch

Take Action

Organize a special project to help Friends of Orphans, like collecting and donating old bicycles. Discover more ideas at www.frouganda.org.