Richard Teka & Shannon Murphy | Kibera Girls Soccer Academy

Richard Teka & Shannon Murphy

A Field of Dreams

The first question that comes to mind when you meet Richard Teka is “Why?” Why would he choose to live and work and raise a family in Kibera, the largest and most infamous urban slum in Africa? For Teka, as he’s known, the answer is simple. It’s home.

Teka grew up in Kibera until he was 7 when his father sent him to school in a rural area of Kenya. But by the time Teka reached high school, his father couldn’t afford the tuition. So Teka returned to his childhood home where hundreds of thousands of people live in desperate circumstances. Kibera, in Nairobi, is a sea of mud-walled shacks with virtually no access to water, toilets, electricity or medical care, where there is rampant abuse of drugs and cheap alcohol, and widespread cases of HIV/AIDS.

After graduating from high school in Kibera, Teka found work teaching life skills to young people and educating them about avoiding AIDS and drugs. It was while doing that that he met another child of Kibera, Abdul Kassim, who had begun a soccer club for girls to help level the playing field with boys. But Abdul knew that the girls needed more than soccer to break the cycle of poverty. So, in 2006, Abdul founded the Kibera Girls Soccer Academy, a high school where girls from desperately poor families could be educated for free.

Teka signed on to teach math, becoming one of the first two teachers at the school, working for no pay.

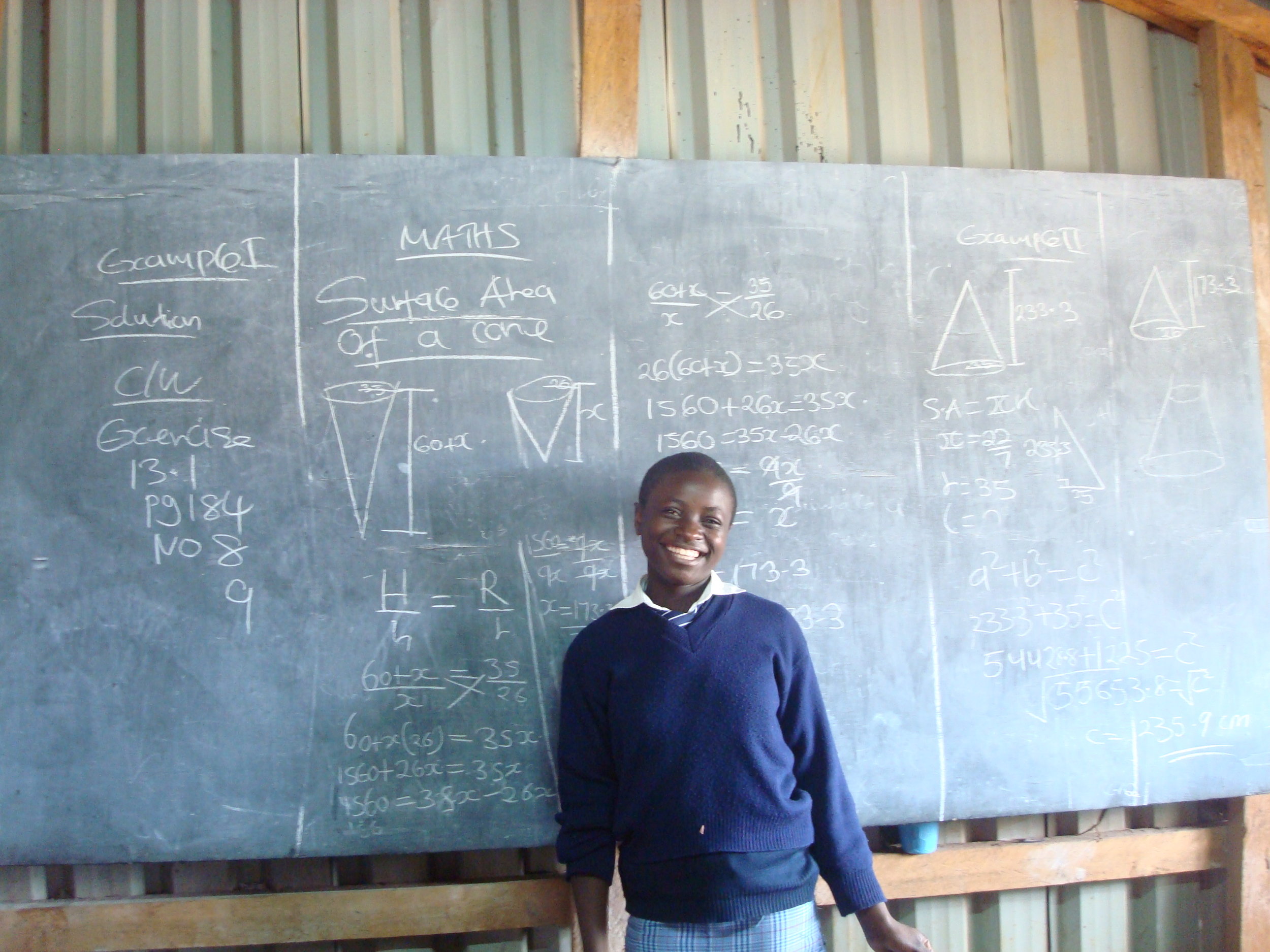

A KGSA student in math class

“I thought if I just taught math their hopes of a future would be diminished. So I taught 8 subjects to girls who were almost my age. Some were bigger than me. But they were more than willing to learn.”

Teka’s father wasn’t impressed. He demanded that Teka get a paying job. But Teka refused to give up teaching so his father kicked him out of the house.

“It was the girls who made me stay [in teaching],” Teka says. “They could be my sisters or my mother. My mother was more educated than my father but she didn’t have any work and my father never gave her money because he had another wife, which is allowed in Kenyan society. I didn’t want these girls not to get a high school education because of money. I didn’t want them to rely on their husbands for money.”

Since opening day, the Kibera Girls Soccer Academy has grown from 13 girls learning in one room, to 130 girls in a two-story building, receiving a free, rigorous education, a variety of artistic and athletic after school activities, and financial training to help improve the economic security of their families.

KGSA's students gathered for a presentation

And Teka has grown too. He is now KGSA’s Program Director, as well as a college graduate, having earned his bachelor’s degree in Commerce and Finance from the University of Nairobi.

“I wanted to work in a bank, but being in Kibera changed my vision. Most people are suffering. My mission is to make Kibera a better place for them.”

Shannon Murphy found her way to Kibera along a much different path. She grew up in rural Wisconsin, with loving, church-going parents who believed that you should help others to have the opportunities that you have had. With that seed planted, Shannon first struck out for adventure, going to college in Hawaii and then joining the Peace Corps after graduation where her assignment surprised her.

“I was sent to Bulgaria, the cushiest Peace Corps experience of anyone. I was not living in a mud hut. I had an apartment and hot water. But I feel that’s where I grew up a little bit more, I began to understand the complexities of the world.”

“My hometown was 99% white, Christian, all very much the same and going to the Peace Corps, I really started understanding the Bootstrap Theory.”

The theory says the best way for people to rise in society is to create their own opportunities, essentially pulling themselves up by their bootstraps. But that didn’t jibe with Shannon’s observations.

KGSA's business club receiving Junior Achievement Entrepreneurship Award

“People in Bulgaria were working so hard and yet they were poor. Systemic oppression was keeping them in poverty. I began to understand the greater picture. I saw racism firsthand working with Roma people [commonly called Gypsies]. Some Bulgarians grow up dehumanizing Roma people as dirty, smelly and lazy. I didn’t have that preconception. It was eye opening.”

It was also the inspiration for Shannon to pursue a career in international development with the goal of addressing poverty on a larger scale. Her path ultimately led her to work for KGSA as the Executive Director of its Foundation, raising funds from her office in Boston to support the school’s mission and vision.

KGSA students gather outside of school

“What attracted me, what I love about their model is that local people are running the school.”

Shannon says construction will begin shortly on a Dormitory that will provide 80 girls much needed housing and meals, in addition to a computer lab, a performance space, an indoor soccer pitch and a rooftop garden. Seeing such tangible progress, Shannon can’t help but reflect on the inspiring words of a KGSA colleague.

“In my life I’ve learned I may not be able to change the world but I can change the world for these 130 girls at the school. The problems are overwhelming but this is what I can do.”

And although 7-thousand miles separates Boston from KGSA in Nairobi, Richard Teka is on the ground there, working hand in hand with Shannon to brighten the future for the girls of Kibera.

“It’s home for us and the girls. They didn’t choose to be born here. I tell them we cannot be sad at our home; that we can only make Kibera a better place; that women can make a difference in society. I want to help the girls achieve their dreams.”

Watch

Take Action

Make a “Classroom Connection.” Do it alone or team up with friends to sponsor a Kibera girl for a year of education. Details at KGSAFoundation.org